The Fansteel Sit-down Strike of 1937

The Fansteel Sit-down Strike of 1937 - Waukegan & North Chicago Workers Fight for their Labor Rights

The 1930s were a time of major unrest across the United States. World War II was brewing across Europe and the Pacific. Fascism was rising and thousands of Americans signed up to fight back. At home, the Great Depression was straining the lives of many families as people struggled to keep basic necessities like housing and food. To make matters worse, many American laborers were working long hours for crumbs at tough and dangerous jobs. Outlooks were bleak, and most Americans had little hope for the future. Yet underneath all this misery, there were sparks of hope stirring, including right here in Lake County.

As times got tough, people sought support in many ways. One of the major avenues were unions. Labor unions were seeing a surge in both support and action during the Depression. With the passage of the Wagner Act in 1935 - which gave workers the legal right and protections to form a union by President FDR, many workplaces were forming unions for the first time, more than doubling the nation’s union density over the course of the following decade. Members were also going out on strike for better wages and conditions across the Midwest. Many were utilizing an effective new technique: the sit down strike. Workers would lock themselves inside their workplaces, refusing to work, and not letting anyone inside until their demands were met. Sit-down strikes were so effective and feared by company owners during this time. In Detroit, workers used this technique to organize what could be called a “general strike”.

A General Strike is where workers across industries coordinate to shut down all economic activity in a city or region and cut off the flow of profit to the owner class.

In Lake County, workers at the Fansteel Metallurgical Co. in North Chicago decided to join in on this movement, and were met with resistance at every turn. In June 1936, Fansteel began to slash wages. In response, Fansteel workers looked to unionize for the first time ever at the plant. They called up Meyer Adelman, a union organizer for the Congress of Industrial Unions (CIO), for help setting up their own union. Fansteel workers were issued a union charter, Lodge 66 of the Amalgamated Association of Iron, Steel, and Tin Workers. The workers of Lodge 66 applied to use the company’s bulletin boards for posting union notices, but were denied the request. A union committee then presented plant superintendent Anselm with a proposed contract, but he informed the group that they would not recognize an external union.

But the workers did not give up. The union, this time along with Adelman, once more presented the superintendent with a revised contract, but it was refused again. Not long after the meeting, Fansteel circulated a petition among workers for the creation of a company-run union. In response, the company superintendent transferred union president John Kondrath from the tool room to the office as a way to isolate him from the factory’s other employees. Finally, the company hired an alleged labor spy, Albert Johnstone, to disrupt union organizing efforts. Johnstone was accused of joining the union to collect information on the union, acting as a provocateur in order to convince the union membership to prematurely go out on strike and disrupt their current organizing efforts.

While Fansteel tried to undermine the union, it continued to grow, from 91 members in September 1936 to 155 members five months later. One final time, the union approached superintendent Anselm to negotiate a bargaining agreement. According to Anselm, Fansteel believed the Wagner Act, which gave workers the right to bargain with the company and go out on strike, was unconstitutional and would not recognize an outside union. Facing continuous roadblocks and violations of their labor rights in this manner, the frustrated workers decided they’d had enough and decided to take immediate action. On the afternoon of February 16th, about 125 union members fearlessly seized two of Fansteel’s factory buildings and barricaded the doors. The occupation peacefully halted the company’s production and anyone who wanted to leave was allowed to do so. Later that evening, Anselm, a company lawyer, and two policemen arrived at the barricaded doors and requested they be allowed inside. Upon being refused entry, the lawyer notified the striking workers that they were all fired.

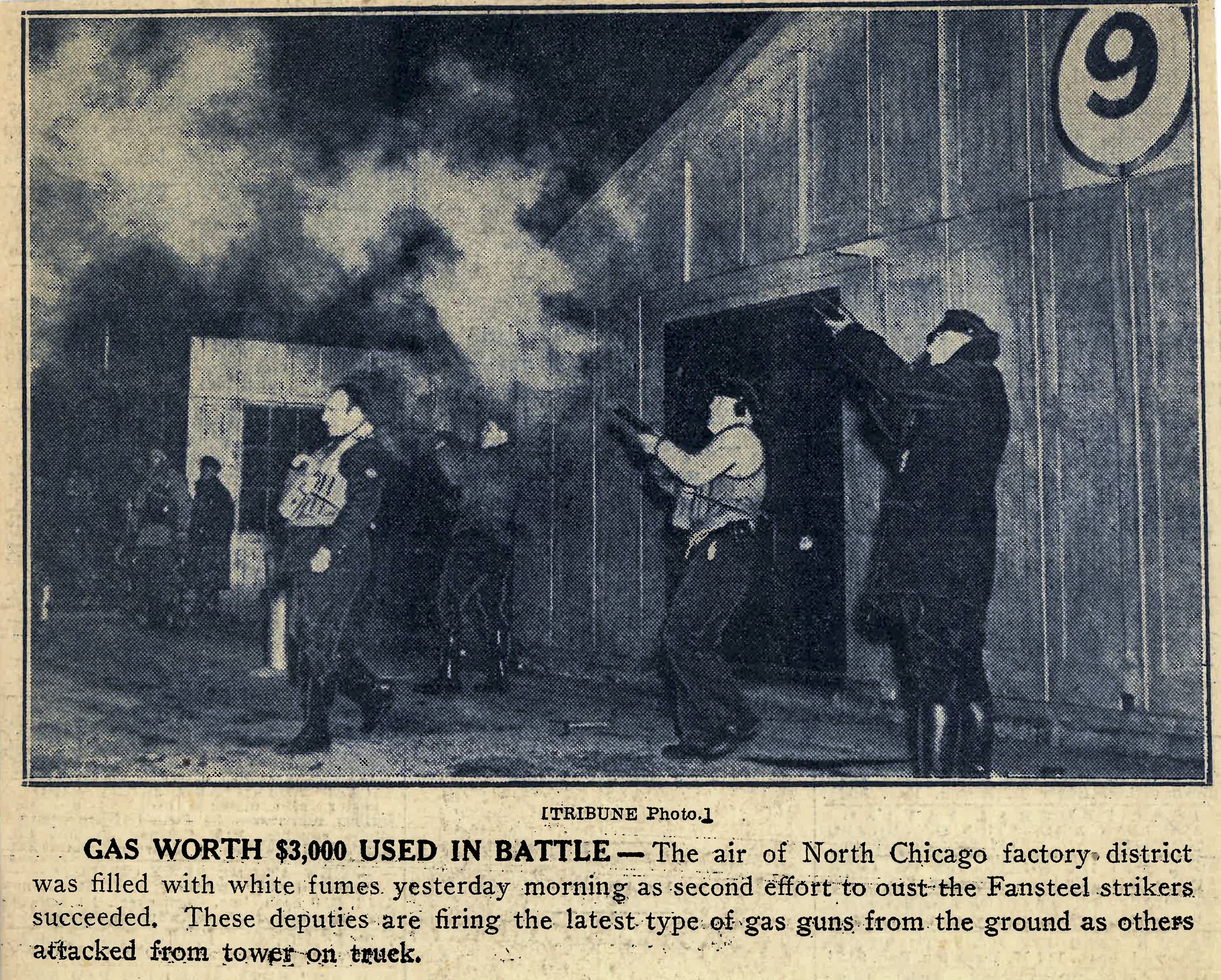

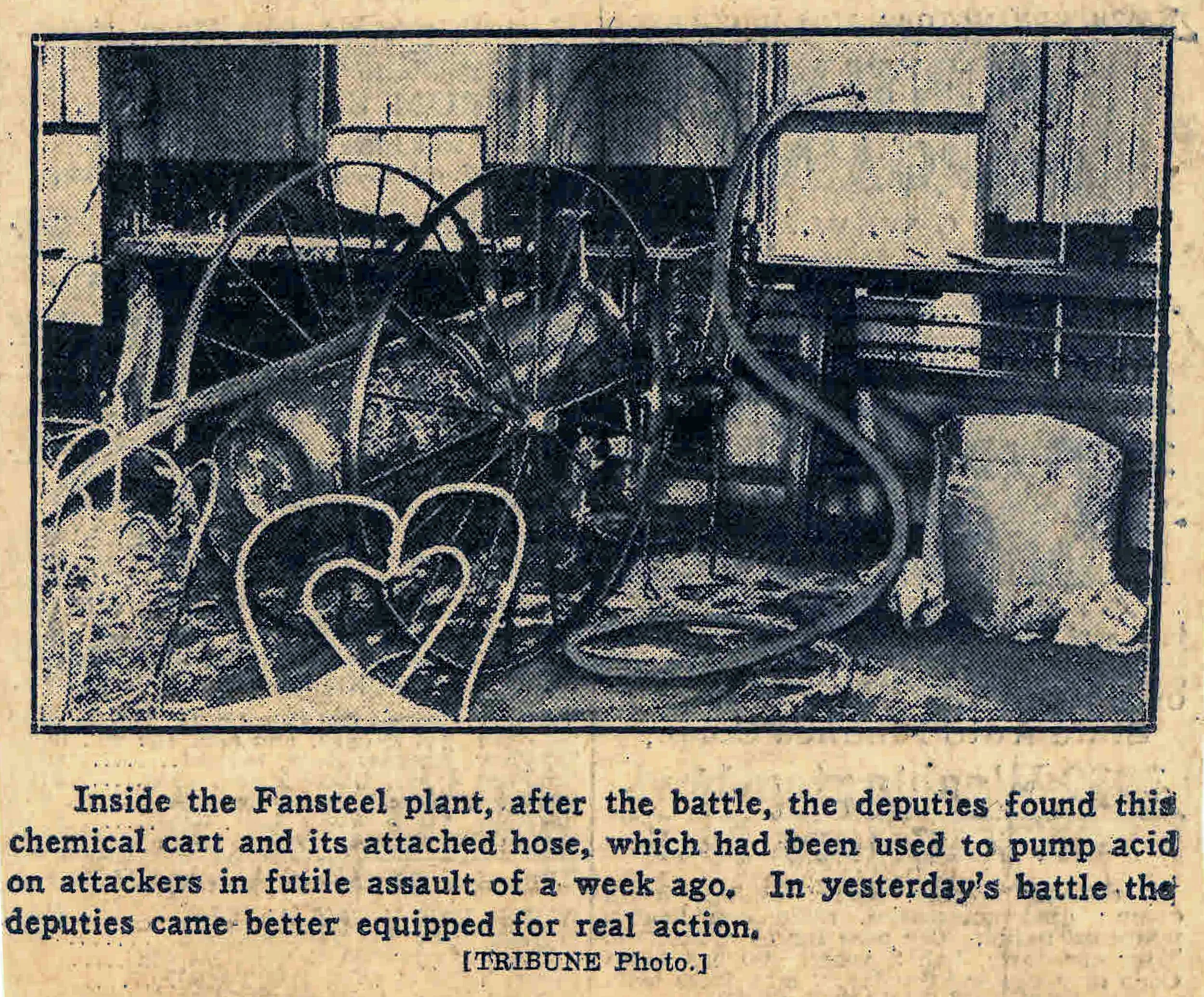

Seeing that the workers were unwilling to leave, Fansteel obtained a legal injunction from the Circuit Court of Lake County calling for the workers to vacate the plant or be arrested. The next morning, the sheriff arrived with 100 deputies and attempted to displace the workers. Deputies used axes, battering rams, and tear gas against the workers. The workers responded in kind to the attacks by spraying sulphuric acid and other chemicals out of the windows and launching homemade projectiles made from heavy metals, tools, and other industrial parts.

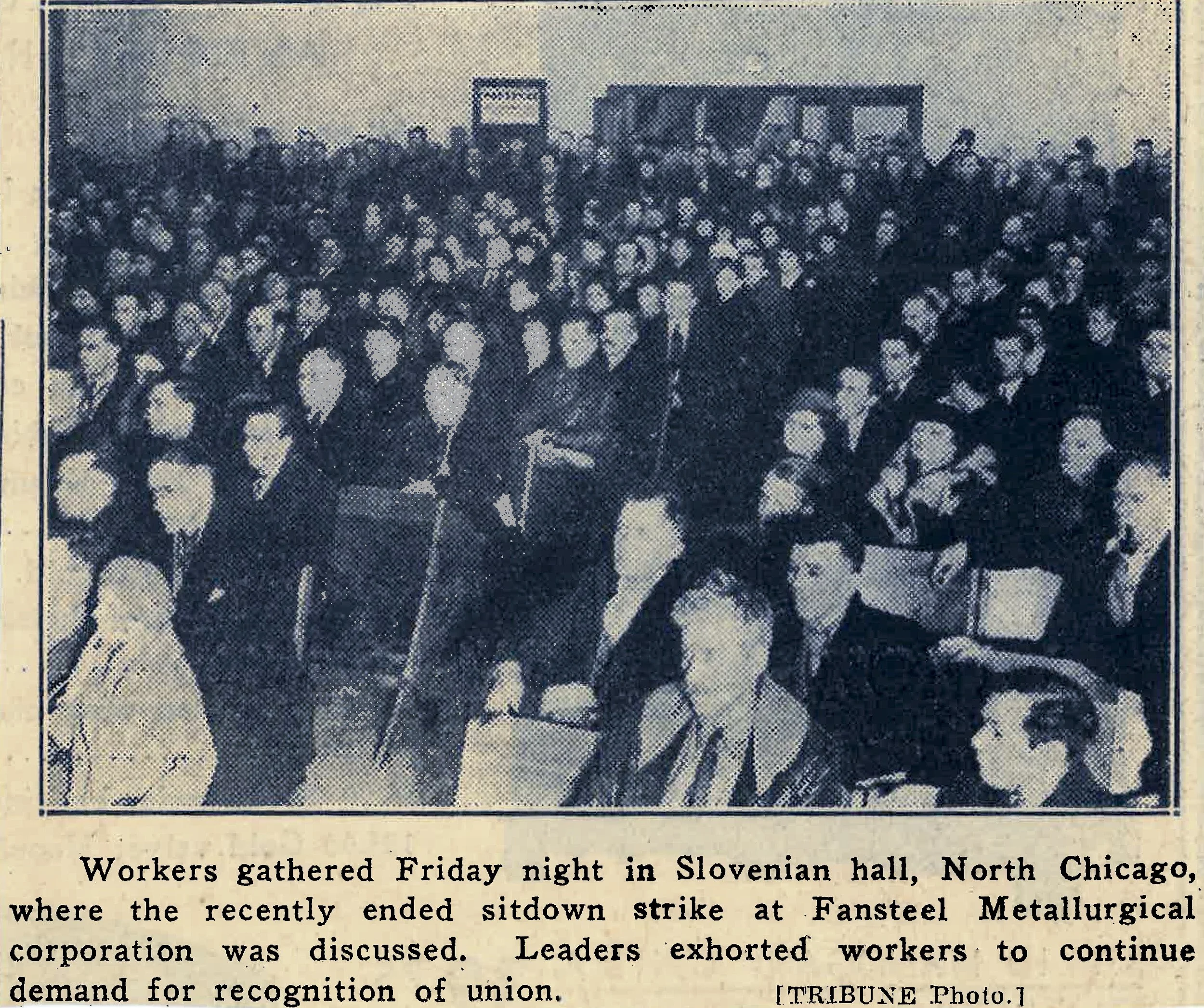

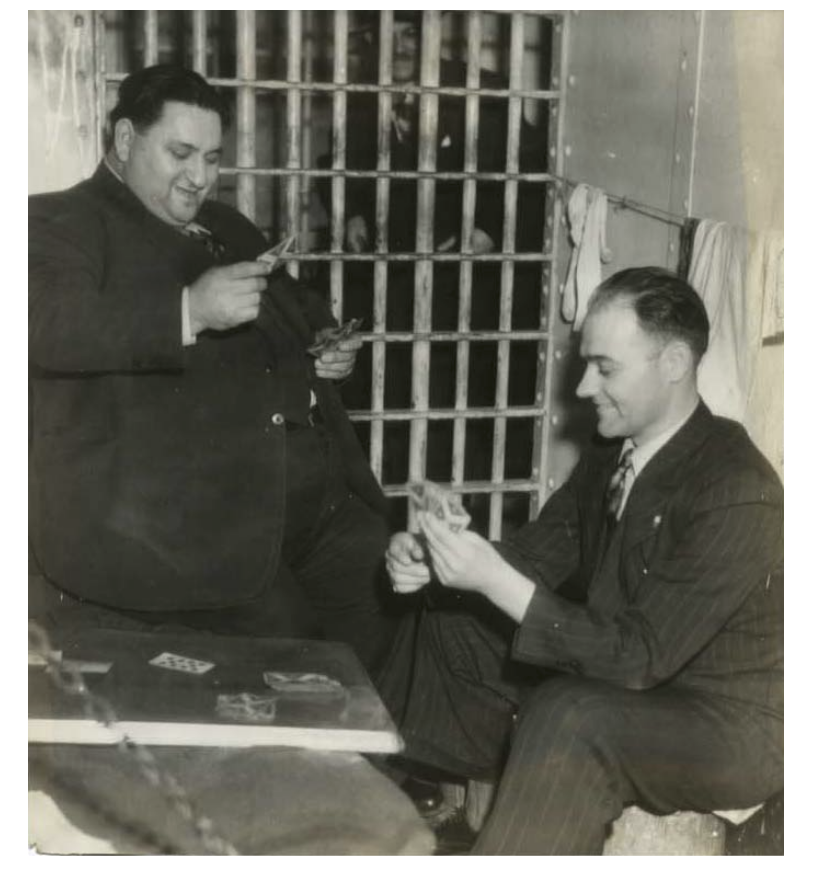

One technique which kept the momentum of the strike going was mutual aid from the community. Only thanks to the continuous assistance of friends, family members, and the CIO who donated food, clothing, bedding, stoves, and cigarettes were the workers able to keep the occupation going. Resistance requires logistical support.Finally, a few days later, the company launched its final attack on the workers in the early morning. Another battle between deputies and strikers occurred that led to the displacement of the workers from the plant. Workers were met with many more deputies and emetic (vomiting) gas which led the workers to abandon the buildings. The owners of Fansteel, having retaken the plant, thusly arrested a majority of the strikers and Adelman.Following this violent end of their sit-down strike - which could have been avoided had the company simply listened to their needs - the workers fought a long battle in court. They eventually got the courts to recognize that Fansteel had violated the workers’ rights to organize a union, but at the cost that many of the fired workers could not be rehired. The Fansteel workers had lost the battle, but eventually would win the war. By the 1950s, workers at Fansteel had formed a number of unions at their factory. Workers across the state had won their right to organize a union on their own terms and negotiate their pay and conditions.

Featured image:

“Waukegan, Ill. - Meyer Adelman and Oakley Mills, officials of steel workers organizing a committee, C.I.O., played cards as they started serving 240 and 180 day jail sentences, respectively, here today for ignoring an injunction forbidding a sit-down strike against the Fansteel Corp., in 1937. Eleven others also started their jail sentences on similar convictions.” (Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum)Lake County residents can learn much from this part of their history. We see that the workers used a number of techniques to fight back against their bosses and the police, who are ever on the side of Capitalism, and defend their rights and dignity as workers. Many of these mutual aid, outreach, and resistance techniques are still potent now, and can be just as helpful at tackling the current struggles Lake County residents face today. One prominent example are the continuous, unwelcome raids by ICE. During these raids, barely-trained agents single out individuals with legally dubious criteria, much as Fansteel isolated John Kondrath from his workers, and quickly arrest them, disappearing people from their families. In both instances we can see that police act on behalf of the ruling class, not by the letter of the law, which nominally gives rights to unions and migrants alike.

But when the community comes together to surround ICE agents with noise and camera lenses, they often become overwhelmed and focus their attention on the crowd instead. Similarly, many immigrants who were fearful of leaving their home to work and run errands had their worries eased with the help of the community. Undocumented residents were able to stay indoors while the community provided mutual aid: food, clothing, money, picking up their kids from school, etc. It’s through the continued application of these techniques that the legacy of Lake County’s working class history lives on. We should continue to look towards our heritage for inspiration as we carry on these struggles in the present and the future. Though mainstream media only covers our failures, our successes are what hold communities like Waukegan together. The workers at Fansteel eventually regained employment, and so too will we remove ICE’s presence here if we continue to build a movement together.

Featured image:

“Strike Breakers (Company Violence)”, 1937 - A painting by Chicago artist Morris Topchevsky memorializing the Fansteel Sit-down Strike and the repression workers faced from the police